Books and textual artifacts have been frequent catalysts in Gothic and horror literature. H.P. Lovecraft’s characters have The Necronomicon and Francis Wayland Thurston discovers dark truths he cannot live with in his dead uncle’s notes in “The Call of Cthulhu” (1928), while the Overlook Hotel seduces Jack Torrance with a pile of historical documents in Stephen King’s The Shining (1977). Offering detailed chronicles of the past—whether recent or ancient—and forbidden knowledge that can be achieved in no other way, these books serve as both repositories and doorways.

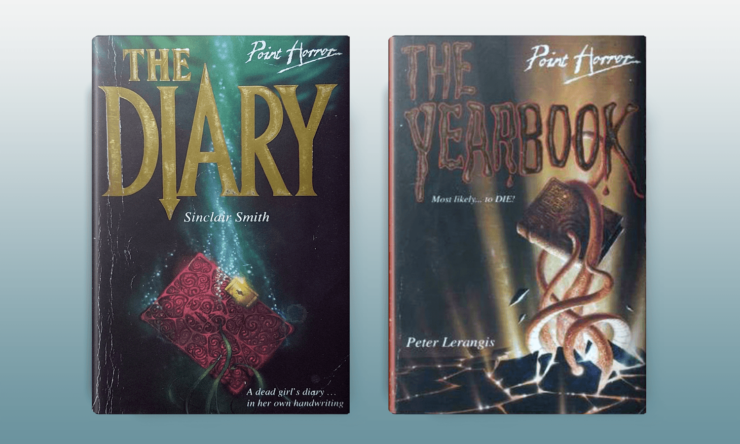

Books bursting with dark secrets play a similarly pivotal role in Sinclair Smith’s The Diary (1994; also published as Let Me Tell You How I Died) and Peter Lerangis’ The Yearbook (1994).

In Smith’s The Diary, Delia Monroe is a devoted diarist, carrying her journal with her everywhere and chronicling the details of her daily life. She also uses it as a writing exercise, following the advice of her English teacher Mr. Parrish, who told her that it’s good practice for an aspiring author to approach diary writing like novel writing, at a bit of an objective remove and with minor embellishment. This raises some concerns about Delia as a potentially unreliable narrator–though none that are ever fully developed or directly addressed. In the novel’s opening pages, Delia is at a sleepover, dreaming about reading a diary whose entry begins with the ominous lines “Let me tell you how I died” (1, emphasis original). Her friends wake her up from this nightmare and she is unnerved to realize that she “had been reading about someone’s death in a diary. And the handwriting was my own” (1-2, emphasis original). She keeps having the dream as well as inexplicable moments of deja vu, such as when she passes a shoe store and vividly remembers buying red shoes for the prom, something she never did. The symbiosis between Delia and the dead girl gets serious when Delia discovers a copy of the diary from her dream in her locker and becomes obsessed, finding herself drawn into the other girl’s life.

The diary girl is named Laura and isn’t actually very nice. In an echo of Delia’s own situation (she lives with her stern elderly aunt) Laura lives with her strict grandmother. Laura daydreams about her grandmother having an accident and she’s incredibly jealous of her “Goody-Two-Shoes” cousin (39), who caters to her grandmother’s needs and is doted on as the favorite grandchild in return. Delia finds herself drawn to an abandoned house in a neighborhood she’s never seen before, only to have the creepy old man next door tell her that the girl who used to live there died, murdered by one of her friends. Delia is more of a “Goody-Two-Shoes” herself, but as she reads more of Laura’s diary, she begins to enjoy how much fun it is to be bad, how liberating it is to free herself from the expectations of others. Delia begins taking on elements of Laura’s personality and breaking rules–lying, pulling mean pranks, and cutting class. She also decides it’s time for a dramatic new look and heads to the Doorway to Beauty hair salon to see Rose, a hairdresser who came and did a night class at the high school. Delia ends up unknowingly having her hair cut and colored to match Laura’s own (though it takes three appointments, as Delia keeps being plagued by a nagging feeling that it’s not quite right). While working on an assignment for school, Delia talks with a librarian named Natasha and spots a group photo from a long-past beauty pageant that Laura actually won–photographic proof that she really existed. This is further validated by Natasha’s memories of Laura. This is a moment of intense realization and conflict for Delia, who is shaken to recognize her new haircut in the dead girl’s photo and she decides to pump the brakes on her transformation, going back to Rose to have her hair dyed back to its original color, though Rose “accidentally” dyes it a dramatic red, bringing Delia even closer to being Laura’s doppelganger.

Buy the Book

Lost in the Moment and Found

While Delia suspects several people over the course of the novel—including her own unreliable perceptions—in the end she discovers that Laura was murdered by Rose, who is actually the nameless Goody-Two-Shoes cousin from Laura’s diary. Rose recognized Laura’s spirit in Delia’s body during the night class and over the course of all those hairdressing appointments, intentionally made Delia look just like Laura, and is ready to kill her all over again. As Rose leads Delia through the woods to the edge of the lake where she plans to drown her again, she asks her “Why’d you have to come back after so many years? You should have left well enough alone, Laura” (178). This complicates the timeline and potential causal relationship between events a bit, because this class takes place well before Delia herself feels Laura’s presence or begins having the diary dreams. The Diary doesn’t follow the traditional cursed object narrative where the connection is forged through possession of the object, because the diary shows up in Delia’s locker after she begins having the dreams and as she discovers in her final confrontation with Rose at the lakeside, Rose herself put it there after recognizing Laura in Delia. As Delia discovers when she goes to visit Laura’s grave, Laura’s death day is Delia’s birthday, so it could be that Laura’s spirit chose Delia’s infant body as a vessel—which raises a whole lot of cosmological questions about how the world works—but remained dormant until the encounter with Rose brought her back to an awareness of herself and to the forefront of Delia’s life.

In the end, it all comes back to the diary, though, as Rose confesses at the police station that she killed Laura because she knew how dangerous she was and all about the “bad accidents” (187, emphasis original) Laura caused, insight she gleaned from reading Laura’s diary. In the novel’s closing chapter, it’s Delia’s diary that makes for some interesting reading, as she notes that “I no longer feel as if there’s a struggle between a living personality and a dead one going on inside me” (188). It could be that Laura has taken over completely, that Laura and Delia’s personalities have synthesized, or that after avenging her murder Laura is now at rest, while Delia is stronger and more confident—and perhaps morally compromised—after surviving this ordeal. All we know for sure is that she’s decided she likes her hair the way it is and that Delia’s Aunt Gracie is dead, having had a “bad accident” (189, emphasis original).

While the purpose of Laura and Delia’s diaries is private and introspective, in Lerangis’ The Yearbook, the intended purpose of the eponymous book is public and collective, commemorating the 1994 class of Wetherby High (which may or may not be a bit of a shout-out to the idealized high school world of Archie Comics and Principal Weatherbee). The protagonist and first person narrator David Kallas joined the yearbook committee for the most noble of reasons: to try to hook up with yearbook editor Ariana Maas (even though they’ve never actually spoken and she has a boyfriend named Stephen Matthew Underwood-Taylor, who everyone adorably calls Smut for short). In the prologue, David begins with what just might be the end of the world, then goes back to the beginning from there, with his account interspersed with sections from the point of view of a mysterious character named Mark.

David works hard on his new yearbook duties and even volunteers for the work no one else wants to do, like running to the printer’s to proof the final pages before production. He decides to get there by cutting through The Ramble, a greenbelt-type wilderness area between the neighborhoods, not because he fancies a forest stroll but because it’s also where teens go to park and make out and he wants to have a peek at Arianna and Smut on his way past. When he finds the horrifically depleted remains of one of his classmates named Rick Arnold—just the skin, with bones and tissue all having all been sucked out—it almost serves him right.

David’s classmates keep going missing and when the yearbook comes back from the printer with some odd, definitely non-approved additions, there certainly seems to be a connection. While David and Arianna had come up with a humorous Bananahead picture to accompany the names of students who didn’t have their photos taken, when the yearbooks come back, the no-show pictures are instead “a black-and-white photo of a shrunken human face. It was festooned with dried flesh, and blood dripped from its mouth” (76). While this is definitely gross, the personalized poems that accompany the entries of select students are even more unsettling. For example, Rick Arnold’s poem reads “Which ‘Most Likely’ goes to Rick? / He isn’t smart or cool or quick / Or careful, so perhaps that’s why / He’s likely, most of all, to die” (81). There’s no real way to dismiss this as a joke since Rick is now actually dead, which ups the stress level of those other students whose entries have been printed with cryptic, creepy poems.

David hits the library to dig into Wetherby’s history to see if there are any clues there, inspired by an earthquake and a similar rash of disappearances in 1950. The librarian, Mrs. Klatsch, grants him access to the restricted section and special collections, which is where all the good stuff is. David digs increasingly further back and finds out about the collapse of a tunnel used for the Underground Railroad in 1862 and the burning of a local woman as a witch in 1686. David’s a smart guy (he very humbly informs his reader in the prologue that he has a genius IQ) and he paid attention in chemistry class, which leads him to the realization of the half-life of evil, as some monstrous presence is returning to prey on Wetherby with increasing frequency. This evil is formidable but also fallible, as David and Ariana discover that the rotation of students slated to be murdered is off by one, because the monsters didn’t adjust their poems to account for a girl who moved and transferred schools (lucky duck Sonya Eggert), so the poems are all for naught, as far as predicting future deaths goes, anyway.

Wetherby High School is in Massachusetts, smack in the middle of Lovecraft country–and the evil that David and Arianna uncover is appropriately Lovecraftian, with a monster emerging from a pit beneath the basement of the school, complete with a cabal of cultists who sing to and serve it, which includes yearbook advisor Joel DeWaart and (much to David’s delight) Smut. This many-tentacled creature is named Pytho and is a kind of transplanted Delphic oracle who draws worshipers to her and bends them to her will. Pytho periodically wakes up, collects a number of sacrifices, and chooses one Wetherby resident to absorb into its collective identity, joining high school basketball star Reggie Borden (1950), abolitionist Jonas Lyte (1862), and accused witch Annabelle Spicer (1686), who are hanging around as husked out, co-opted versions of themselves. The monster wants either David or Arianna, neither of whom are keen for the opportunity, so working in collaboration with Police Chief Hayes (who was Reggie’s best friend) and the high school janitor Mr. Sarro, they drive the monster back with the corrosive power of cola, which seems both a very teenage solution to a cosmic problem and is another example of “gee, it’s a good thing David was paying attention in chemistry class.” They set an explosive charge in the hopes of closing the chasm beneath the school, but it ends up being bigger than planned, and in the opening prologue, David fears that “I have destroyed my entire hometown” (vi). After this opening, the rest of the novel takes readers back to the beginning of the yearbook trouble, but in addition to drawing the reader in, this prologue also foregrounds David’s writing of the story that follows, with his account serving as a kind of book within a book.

Throughout The Yearbook, Lerangis intersperses the “David” sections with others that are titled “Mark.” Following these “Mark” sections, David works to piece together what they mean, seeing these narrative asides in his dreams and trying to figure out just who Mark could be. As a young boy, Mark learns that his parents have disappeared and are presumed dead and in one of the later “Mark” sections, he is called on to identify the body of his grandmother and primary caretaker. He is only seventeen when his grandmother dies, so he is placed with a foster parent and moved to nearby Wetherby, which has been “rebuilt … from the ground up” (156-157, emphasis original) and is home to the chemical company where his parents worked and from which they disappeared. These two threads coalesce once the creature’s half-life has come to pass again, in the far-off future of 2016 (ouch), when Mark is going through boxes of his parents’ stuff that have been hauled from his old attic to his new room with his foster father and he finds a stack of their old yearbooks. He flips through the pages, looking at yearbook photos of his parents—David and Arianna—and marveling at all he doesn’t know about their lives. When he opens the fourth and final yearbook, he discovers that the binding itself has been hollowed out and the yearbook pages have been replaced with his father’s narrative, which is identical to The Yearbook, without the “Mark” sections, and Mark settles in to read the story the reader themself has just finished. This story and the clues David has left behind lead Mark to the monster’s lair, where he is reunited with his parents, along with Chief Hayes and Mr. Sarro, to take his place in keeping the monster at bay, a bittersweet ending perfect for a tale of cosmic horror.

In both The Diary and The Yearbook, books play an integral part in the horror that follows, but books also become a way for the characters to claim agency and add their own perspectives to the historical record. In The Diary, Delia falls under the spell of Laura’s diary, but also has the opportunity to tell her own story (though who exactly is doing the telling in the novel’s final chapter is open to interpretation and debate). In The Yearbook, David has a much more impactful role to play in the telling of his own story, which both chronicles the horrors he has discovered and reunites him and Arianna with their son Mark, informing Mark about and drawing him into the cosmic horrors of Wetherby. The horror genre cautions us time and time again about reading forbidden books, questing for destructive knowledge … but who can resist? At least when Delia and David learn things they shouldn’t, they add their own voices to the clamor, contributing a new narrative to this dark tradition, just waiting to be discovered by the next reader who really shouldn’t read it, but definitely will.

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.